Revolutionary Artists

He followed in his father’s footsteps, though his elder was not nearly as talented. The two had a tumultuous relationship, and they eventually became estranged, yet the father made a lasting impression, providing important early training. But the youngster was a rebel, a genius in fact, and he would go on to change the history of his artform. As I am sure you have surmised, this is the story of Pablo Picasso. Ok, it could also be the story of Ludwig Van Beethoven (born December 1770, Bonn, Germany; died March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria).

There is an apt comparison between the two revolutionary artists, and it might be interesting to think about them side by side today as we hear two works of Beethoven, one very early, and one quite late. Beethoven received his early musical training from his bass-playing, alcoholic and at times abusive father; and Picasso from his father, a painter and art teacher who would both encourage and be jealous of his son. Beethoven wrote in the model of Haydn, Mozart, and Bach while Picasso took early inspiration from El Greco, Goya, and Cézanne. Picasso called Cézanne, 42 years his senior, his “one and only master,” while Beethoven’s most famous teacher and mentor Haydn, was 38 years his elder.

This particular alchemy – a budding genius, a difficult relationship with a father, and encountering a profound influence in their early 20s – seems to have affected both deeply. While Beethoven was able to study with Haydn, Picasso knew Cézanne only through his work. Both artists would go on to transform their language and profoundly alter the course of music and art.

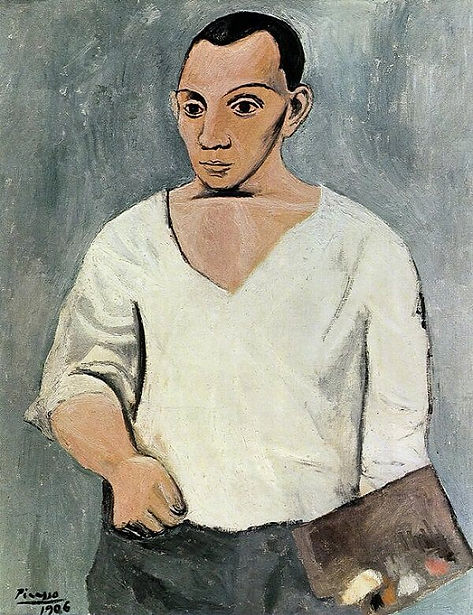

You can already see in this self-portrait painted at the age of 25, the artist Picasso was to become. However, he was still referencing the masters who had come before him, reflecting and building off of his contemporaries, while also incorporating elements from Iberian folk art.

Picasso, Self-Portrait, Age 25

In 1792, Beethoven left his hometown of Bonn to strike it big in the world’s center of music, Vienna. He quickly established himself as a pianist and a composer, bringing along with him three showy piano trios (his Op. 1). Over the next three years, he made his name through private performances, honing his craft with Joseph Haydn, and developing relationships with musicians and patrons alike. In 1795, he made his public debut at a benefit concert for Haydn, performing a Mozart concerto as well as his 2nd Piano Concerto. He was a hit and in demand. In the following year, also at the age of 25, he published his Op. 2, a set of four piano sonatas that were building on the masters of his time, much like Picasso’s early self-portrait.

If someone asked you to play "guess the composer" with Beethoven's Piano Sonata No.1 in F minor, you would be well within your rights if, after the first few bars, you yelled “Stop! I've heard enough - that is, without a doubt, Mozart!" But keep listening, and you begin to wonder, could this be Mozart? Maybe Haydn? No, it’s something else. The opening Allegro contains strange leaps, arpeggios, and harmonic shifts that feel new. There is a gravity and a weight that creeps in that feels unfamiliar. And what about this key of F minor? Haydn never wrote a piano sonata in the key, and of Mozart’s 600+ works, only four were in F minor. The following Adagio brings us into more new territory. A lovely song-like quality permeates, and while the influences of Mozart and his teacher Haydn (to whom the sonata was dedicated) can be heard, Beethoven’s ability to hold his audience in almost perpetual suspense is already on display. The following Minuet is fairly straightforward, but his use of syncopation and sudden pauses keeps listeners on their toes. The closing Prestissimo (not just fast, but really fast), is more recognizably Beethoven than anything we’ve heard so far. Running triplets at the opening and banging chords above – now, here is the voice that would soon change the world of music.

Fast forward to 1817, Beethoven is no longer the fresh face of music in Vienna, though he is still there. Now in his late 40s, fighting for the custody of his nephew, and suffering from deafness and other health issues, Beethoven has seen the world change dramatically. The Napoleonic wars had raged across the continent since 1803 – bombing in the 1809 siege of Vienna came so close to his apartment that he ran to the basement and covered his ears with pillows in an attempt to protect what little of his hearing he had left. Of the invasion, he wrote, “The whole course of events has affected me in both body and soul…What a destructive and unruly life I see and hear around me; nothing but drums, cannon and human misery in every form.” After Napoleon’s final defeat in 1815, a transformed Europe was left in its wake: new territorial borders, the decline of the Spanish and Portuguese empires, the emergence of Britain as the dominant global superpower, as well as the rise of nationalism in Germany and Italy.

During this time, Beethoven’s music had also changed substantially. He left behind his early classical period, for what became known as his “heroic” middle period, ushering in what would come to be known as music’s Romantic period. Napoleon, whose early lofty ideas of throwing off the aristocratic yoke himself provided the rebelliously minded Beethoven with artistic inspiration – so much so that he dedicated his Third Symphony to Bonaparte (though Napoleon crowning himself emperor of France caused Beethoven to use such force in scratching out the dedication on his original score that he left nothing behind except a hole in the paper - see image below). Symphonies 3-8, his last three piano concertos, the middle set of string quartets, the famous “Moonlight,” “Waldstein,” and “Appassionata” piano sonatas, all fall into this "heroic" period, as well. But then things shifted again, and Beethoven entered his “late” period.

Original title page of Beethoven's Symphony 3 with Napoleon's dedication obliterated by the composer

Picasso also had his fair share of artistic periods. His early, somber Blue period of 1901-1904 that often depicted subjects in distress, was followed by a more optimistic Pink period. The Spanish Civil War (1936-39) profoundly affected Picasso and his relationship to his art. His ongoing interest in Iberian and African art, and eventually ancient Greek art, pushed him into new creative territory, resulting in a series of iconic, instantly recognizable paintings, stylistically diverse but unmistakably Picasso.

During the middle of the Spanish Civil War, Picasso, now in his 50s, drew another self-portrait. It displays his understanding of art history and his unique incorporation of it in a new form. Like Beethoven’s late works, his new style was not universally praised, and many found it difficult to understand. Many still do.

Picasso, Self-Portrait, Age 57

Beethoven, for his part, was on to something similar in his late style. Unmistakably his own, he nevertheless was reaching back into the deep recesses of music history to draw inspiration. The Piano Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major, Op. 106, “Hammerklavier” is written at a time of transition, not just for Beethoven, but for the piano itself. During the composition of this piece, Beethoven was gifted a new instrument from London’s Broadwood piano company. Beethoven takes advantage of the piano's expanded range in the final movement of the piece, indicating that the earlier movements were written before its arrival. Though set in a classical four-movement structure, the work stretches and pulls at the conventions to the point of obscuration. Some of this is due simply to its massive proportions – it is longer than many of his symphonies. In addition, the work is a technical and emotional powerhouse, where even today’s pianos (and any pianist foolhardy enough to take it on), strain at the demands. The first movement begins with a bang, wild and unrestrained, quickly shifting into a very quiet repetition of the same musical idea. An early indicator of things to come, now would be a good time to don your supportive neck collar, because whiplash is a real danger. Beethoven seems to be putting it all on the table. Terse by comparison, the following Scherzo provides scant relief, with its agitated main motive skipping about and a central section full of bustling energy. What follows is a vast and deeply felt Adagio, which seems to hold the weight of the world’s sorrows. Instead of launching into the finale, Beethoven provides a flowing slow introduction borrowed from Baroque convention, which after a couple of false starts, launches into one of the wildest finales ever written, complete with a daunting fugue that strikes fear into the hearts of pianists everywhere. Though the soundworlds of Mozart and Haydn are well in the rear window, their DNA, and that of music stretching back to Bach and beyond, are embodied, synthesized, and transformed into a singularly powerful display of human imagination and endurance that, like the art of Picasso, stretches our minds and pushes us to the limits of understanding.

–ML